The determinant has nothing to do with “equations”, it is a scalar.

The determinant is only applicable to square matrices, describing the volume of n n-dimensional vectors. For two dimensions, it is the area. A determinant of zero indicates that the matrix cannot span an n-dimensional space, at most n-1 dimensions, i.e., not full rank. So the volume is zero in n dimensions.

Matrix Rank: Refers to the maximum number of linearly independent rows or columns in a matrix. It represents the number of independent directions that the matrix can describe in space, i.e., the maximum dimension that the matrix can actually express.

Prerequisite: Understanding Matrix Multiplication

Writing #

Taking two-dimensional space as an example, the determinant is written as:

$$ \det(A) = |A| = \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} $$Meaning #

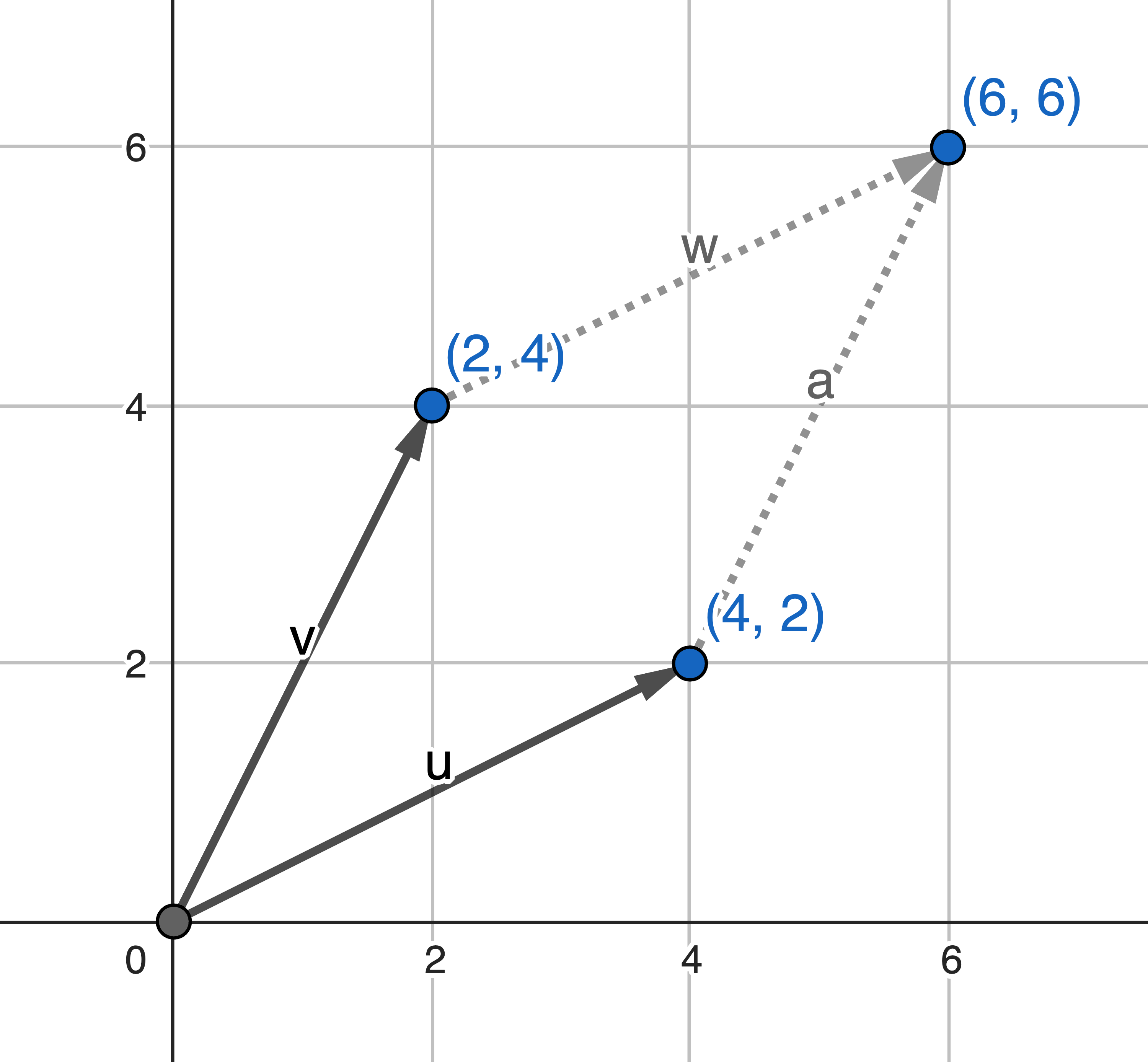

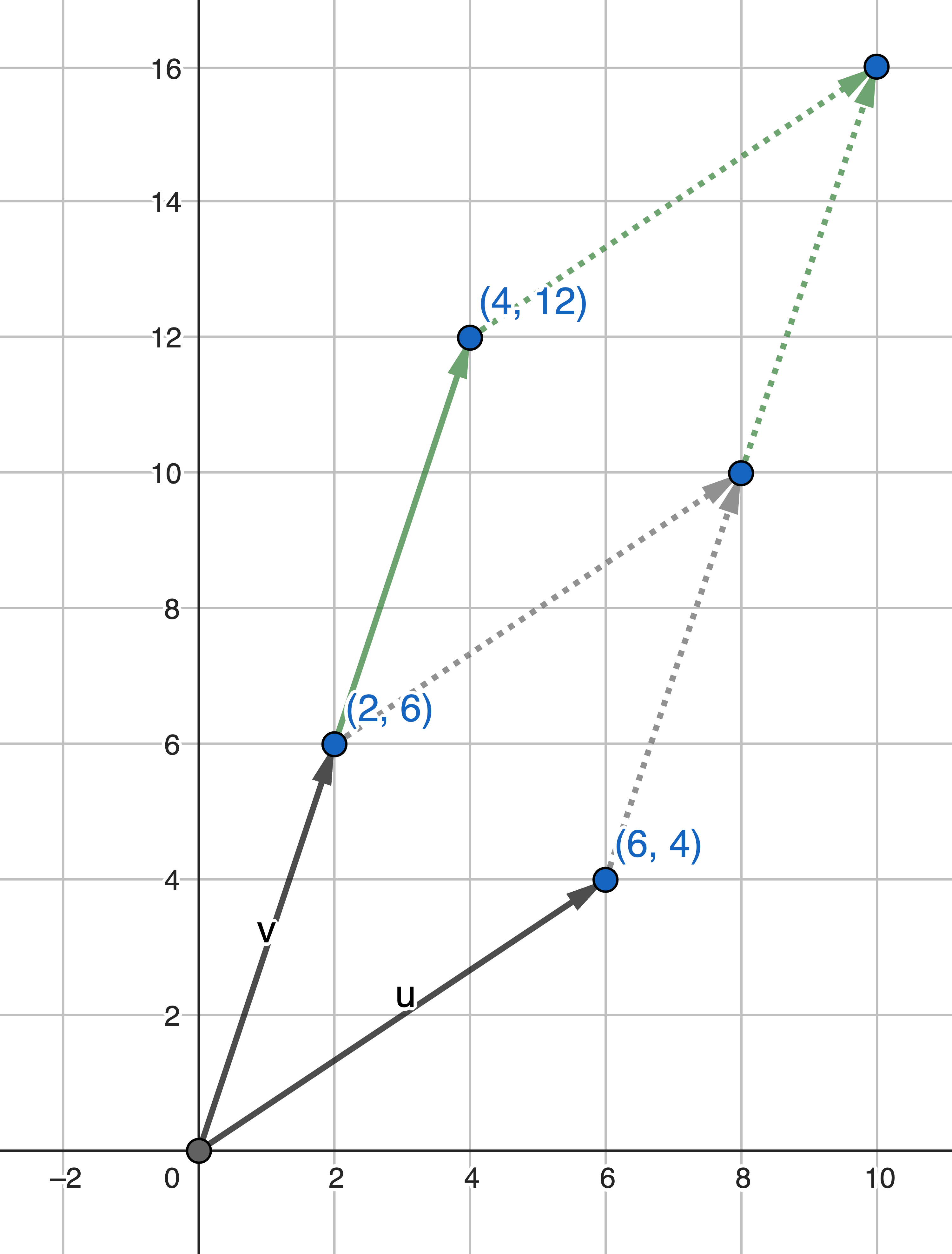

The area enclosed by these two two-dimensional vectors is 12:

$$ \det( \begin{bmatrix} 4 & 2 \\ 2 & 4 \end{bmatrix} ) = 4*4 - 2*2 = 12 $$

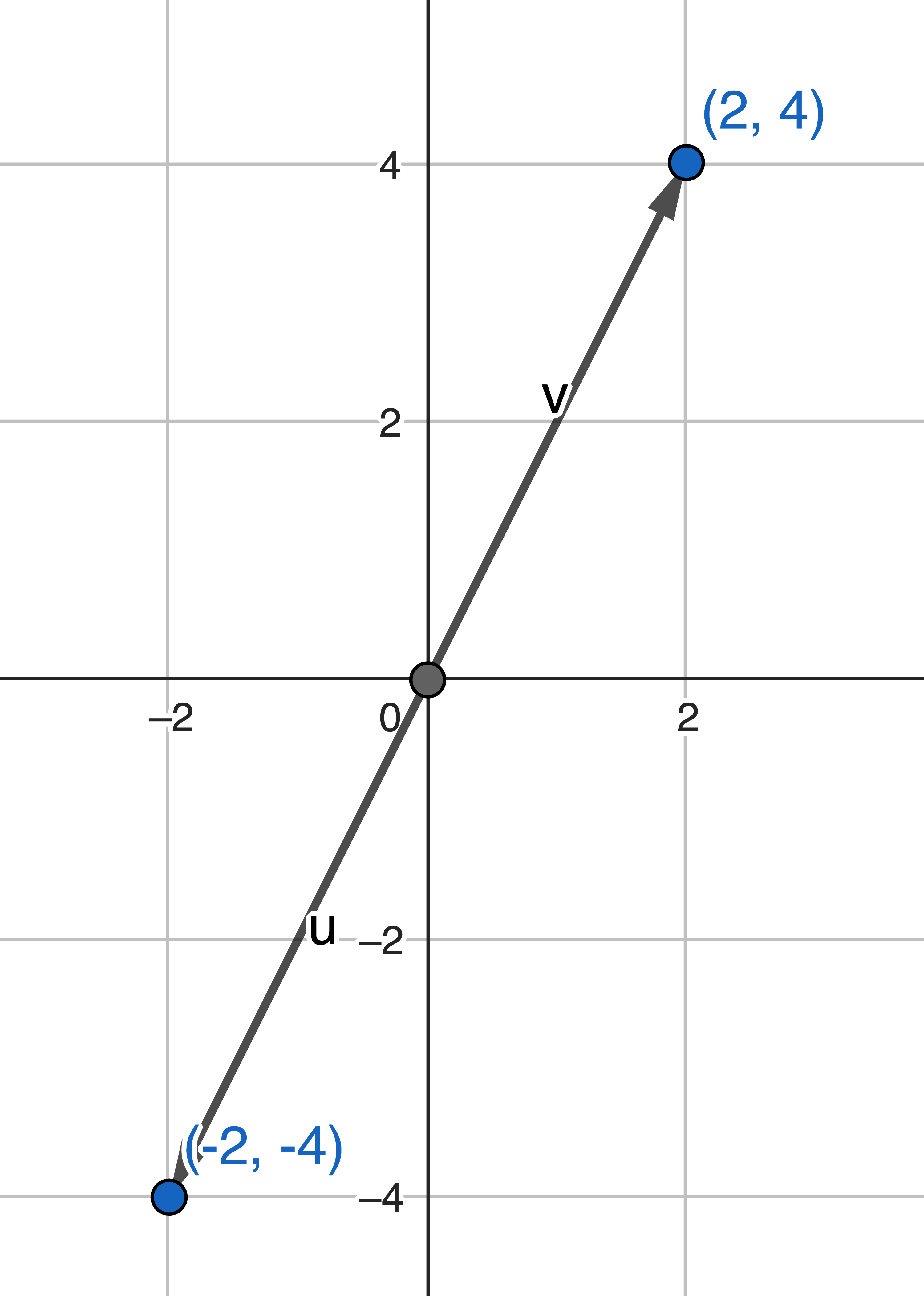

Whereas this matrix, obviously, because the vectors are collinear, the determinant (area) is zero.

$$ \det( \begin{bmatrix} 2 & -2 \\ 4 & -4 \end{bmatrix} ) = 2*(-4) - 4*(-2) = 0 $$

Calculation #

Two-dimensional matrix #

Let’s start with this \(2*2\) matrix. It doesn’t matter whether you write the vectors by row or by column, the result is the same. For example, using column vectors:

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} = ad - bc $$The result won’t change if you write it as row vectors.

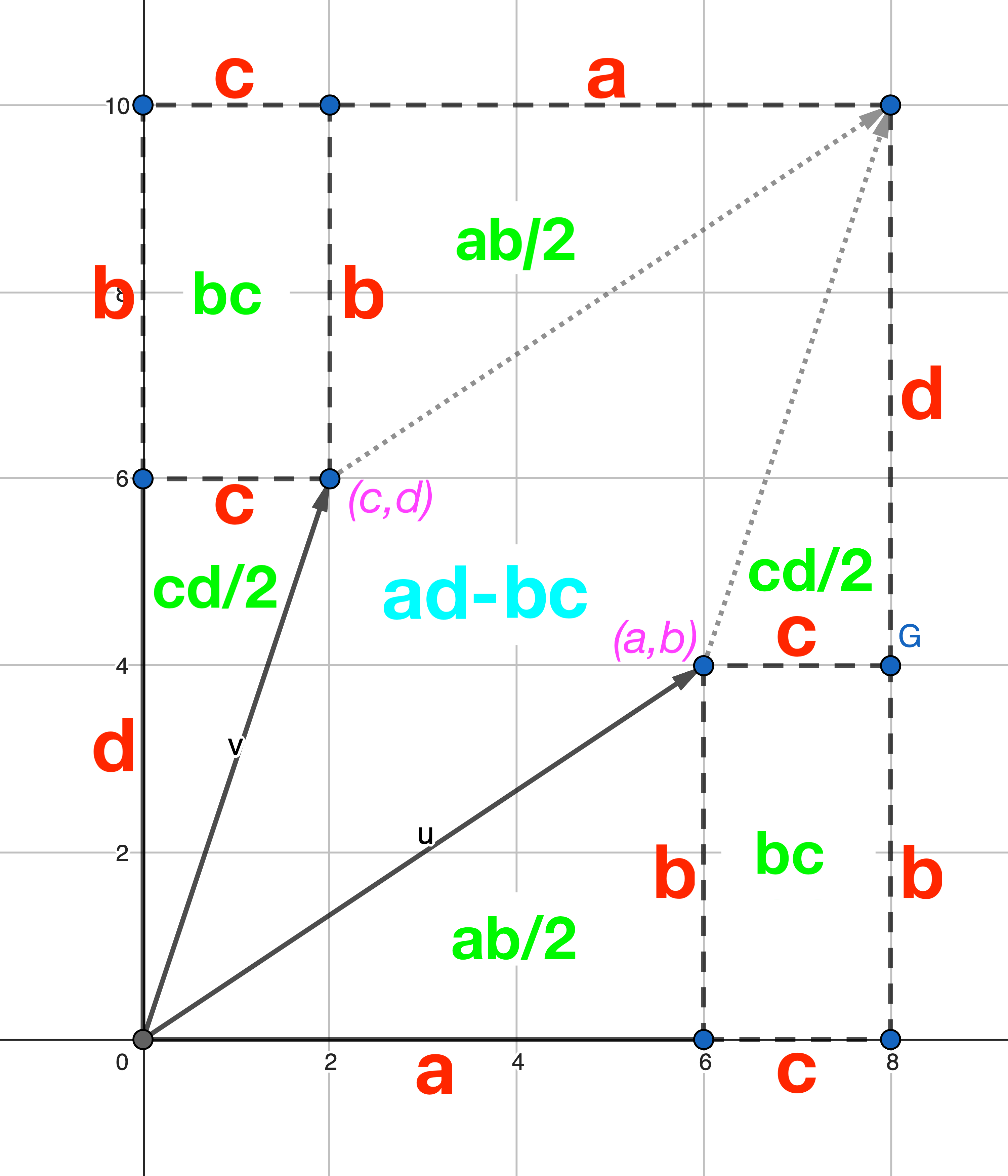

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{vmatrix} = ad - bc $$Why is it calculated this way? First, an intuitive explanation: because the result is actually the area of the parallelogram in the figure below. So no matter how you write the vectors, the area won’t change.

$$ \begin{align} \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} &= (a+c)(b+d) - ab - cd - 2bc \\ &= ab + ad + cb + dc - ab - cd - 2bc \\ &= ad - bc \end{align} $$

But if you swap two columns, the value of the determinant will change sign.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} c & a \\ d & b \end{vmatrix} = cb - ad = -(ad - bc) = -\begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} $$Right-hand rule #

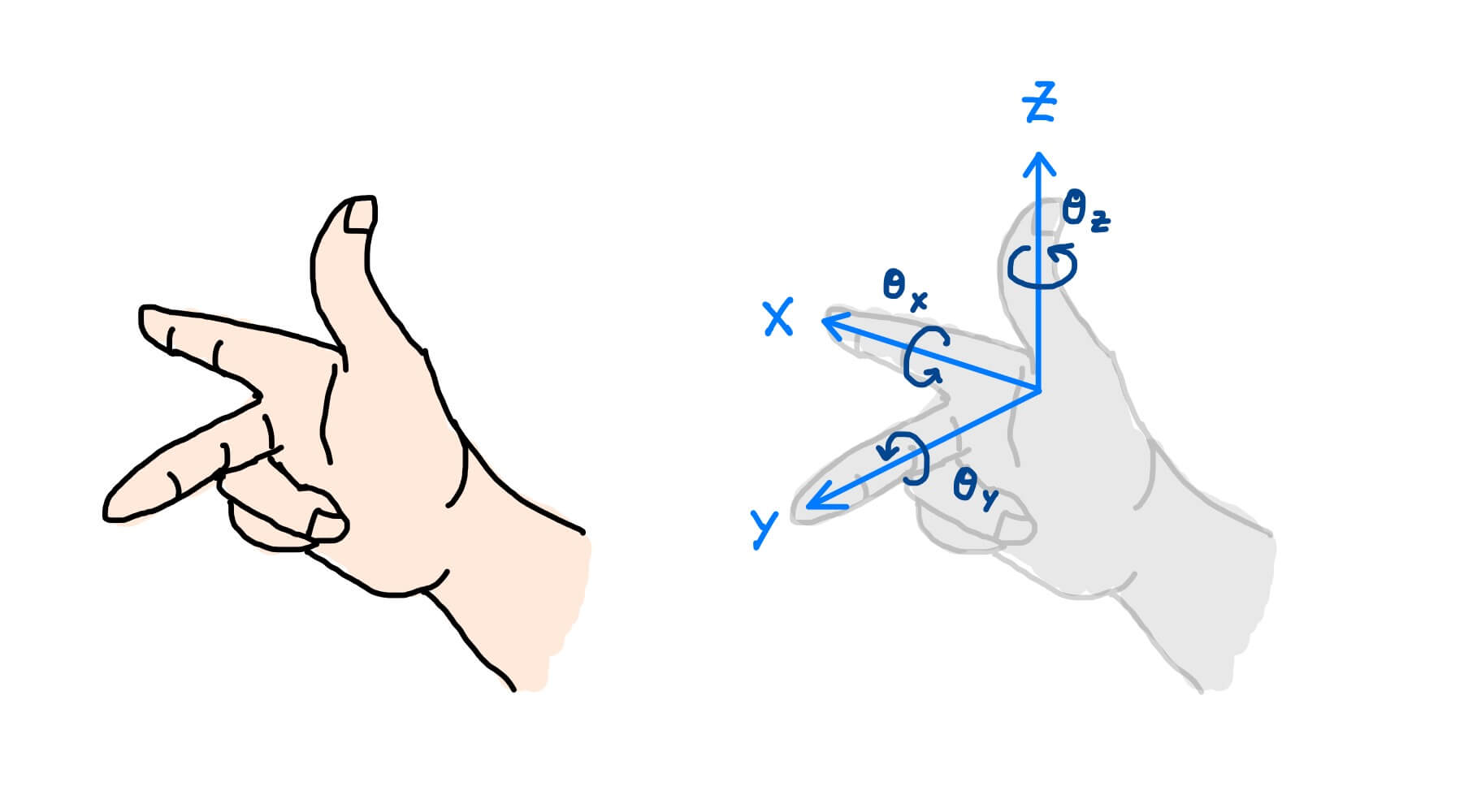

You may still ask, “No, I see the two vectors in the figure above have swapped positions, but the area is still the same, right?” It must be mentioned here that the coordinate space has an absolute direction, which can be determined by the right-hand rule. There is no reason why it has to be the right hand; it has to be defined. The characteristic of the right-hand rule is that when looking down from \(z\), the \(x\) axis (the first dimension) is clockwise to the \(y\) axis (the second dimension).

So the swapping of two columns mentioned above is actually swapping the \(x\) and \(y\) axes, which means flipping the space, so the signed area (volume) will change sign.

Therefore, looking back at the calculation formula for the two-dimensional space determinant, \(a\) is the base on the first dimension, and \(d\) is the height on the second dimension perpendicular to it, multiplying them gives the area. Because the dimensions are equal, the same thing has to be done with \(b\) and \(c\). So adding the two areas is enough:

$$ ad + bc = \text{area1} + \text{area2} $$However, the \(b\) in the second part actually represents the base on the second dimension (it is the \(y\) of the first vector), which means \(bc\) is calculated in a flipped space (by the left-hand rule), and the result naturally carries a sign. To correct this flip, you need to actively multiply by a negative sign.

$$ ad + (-bc) = ad - bc $$Three-dimensional matrix #

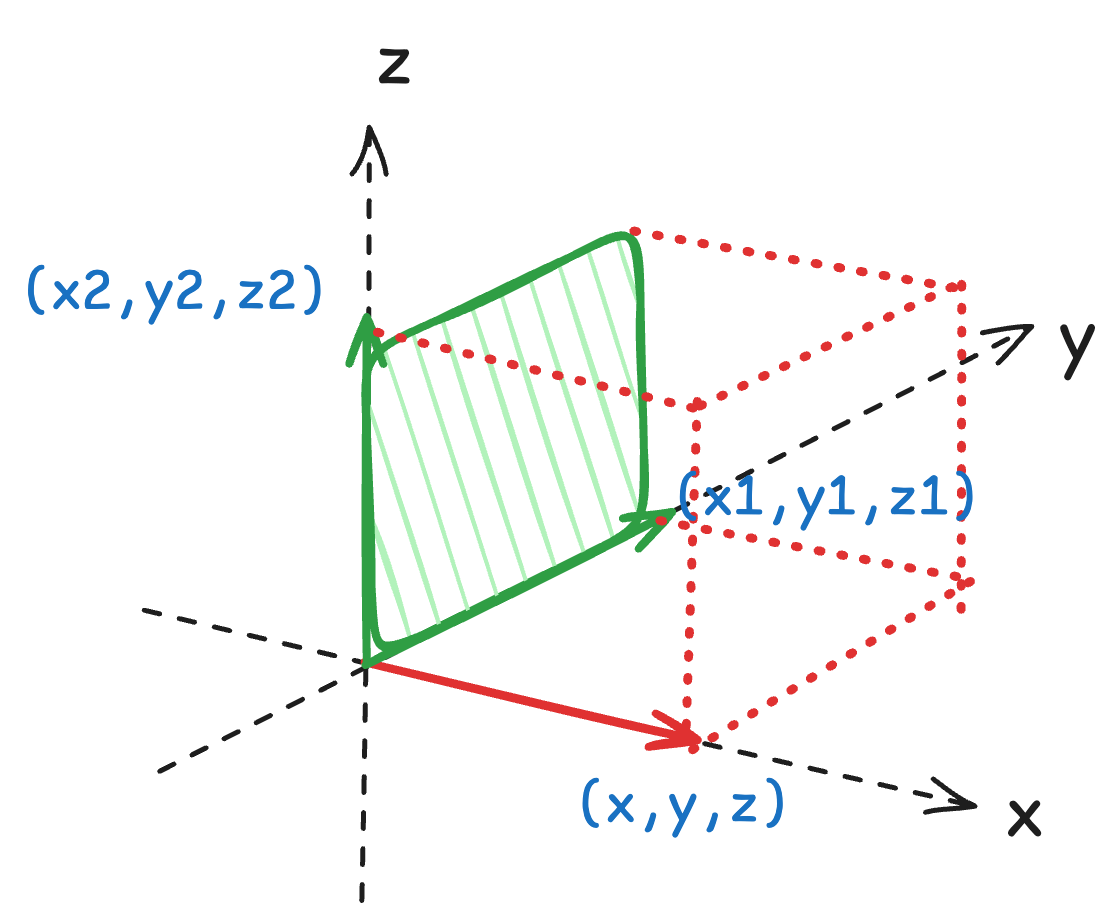

The calculation logic of the determinant of a three-dimensional matrix is similar to that of a two-dimensional matrix, except that a recursive process is needed to reduce it to two dimensions.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} x & y & z \\ x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\ x_2 & y_2 & z_2 \end{vmatrix} = x\begin{vmatrix} y_1 & z_1 \\ y_2 & z_2 \end{vmatrix} - y\begin{vmatrix} x_1 & z_1 \\ x_2 & z_2 \end{vmatrix} + z\begin{vmatrix} x_1 & y_1 \\ x_2 & y_2 \end{vmatrix} $$The above formula can be well explained by a special example. Suppose the three vectors are all on the three coordinate axes, then \(x\begin{vmatrix}y_1 & z_1 \\ y_2 & z_2\end{vmatrix}\) is just the volume of the base in the \(y-z\) plane with \(x\) as the height, and the base area is just the determinant of the corresponding submatrix. Similarly, this calculation step must be done for \(y\) and \(z\) because they are all equal.

Here, the sign alternates again. Why? When looking down from each axis, the base matrix must follow the right-hand rule. For example, when \(x\) is the height, the \(y\) (the first dimension of the submatrix) must be correctly positioned in the clockwise direction of \(z\), following the right-hand rule, so no negative sign is needed. The same is true for the direction of \(z\) as the height. But when \(y\) is the height, the \(x\) in the base \(x-z\) plane is in the counterclockwise direction of \(z\), violating the right-hand rule, as if it were in a flipped space, so a negative sign is needed to correct it.

Laplace Expansion #

This recursive process can be extended to \(n\) dimensions, which is the Laplace Expansion. This expansion process involves multiplying each element in the matrix by its algebraic minor, where the algebraic minor has a sign factor in front of it, which is the so-called alternating positive and negative sign.

Minor #

To a certain element \(a_{ij}\) in the matrix, its minor \(M_{ij}\) is the determinant of the submatrix obtained by removing the \(i\)th row and \(j\)th column. For example:

$$ M_{11} = \begin{vmatrix} y_1 & z_1 \\ y_2 & z_2 \end{vmatrix} $$Algebraic Minor #

For the element \(a_{ij}\) in the matrix, its algebraic minor \(C_{ij}\) is the minor multiplied by the corresponding sign factor. The calculation formula for the algebraic minor of the matrix element \(a_{ij}\) is as follows:

$$ C_{ij} = (-1)^{i+j}M_{ij} $$So for a \(3*3\) matrix, the Laplace expansion is:

$$ \begin{align} \det(A) &= a_{11}C_{11} + a_{12}C_{12} + a_{13}C_{13} \\ &= a_{11}(-1)^{1+1}M_{11} + a_{12}(-1)^{1+2}M_{12} + a_{13}(-1)^{1+3}M_{13} \\ &= a_{11}M_{11} - a_{12}M_{12} + a_{13}M_{13} \end{align} $$Properties #

Multiplication #

If you multiply one row (column) by a scalar, the determinant will also be multiplied by the same scalar. This is because it is equivalent to nudging one side of the parallelogram.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} ka & c \\ kb & d \end{vmatrix} = k\begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} = k(ad - bc) $$

If the entire matrix is multiplied by a scalar \(k\), the determinant will be increased by a factor of \(k^n\). Remember, matrices have dimensions.

$$ \det(kA) = k^n \det(A) $$Addition #

If you add one vector to another, the determinant will also be added. This is equivalent to superimposing two parallelograms with the same base.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a + a' & c \\ b + b' & d \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} + \begin{vmatrix} a' & c \\ b' & d \end{vmatrix} = ad - bc + a'd - b'c $$Identity Matrix #

The determinant of the identity matrix is 1. This is the most beautiful property, meaning that it does not transform space.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{vmatrix} = 1 * 1 - 0 * 0 = 1 $$Zero Determinant #

A determinant of zero is an important characteristic, indicating that the matrix cannot span an \(n\) dimensional space, at most \(n-1\) dimensions, i.e., not full rank. So the volume is zero in \(n\) dimensions. The fundamental reason is the existence of linearly dependent vectors, i.e., some vectors are redundant, not introducing independent information about that dimension.

Existence of the same vector #

First of all, the determinant of a matrix with the same row (column) is zero. Obviously, the vectors overlap, so what volume?

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a & a \\ b & b \end{vmatrix} = a*b - a*b = 0 $$One vector is a multiple of another #

The above-mentioned scalar multiplication property tells us that \(k\) can be extracted, resulting in a matrix with equal vectors.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a & ka \\ b & kb \end{vmatrix} = k\begin{vmatrix} a & a \\ b & b \end{vmatrix} = k*0 = 0 $$Existence of zero vector #

This is actually a special case of the above \(k=0\). (One less dimension of information, of course, zero volume)

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a & 0 \\ b & 0 \end{vmatrix} = a*0 - 0*b = 0 $$Linear dependence #

One vector is a linear combination of the other vectors, resulting in redundant vectors. This equation uses the above addition and scalar multiplication properties.

$$ \begin{align} \begin{vmatrix} a & b & k_1a + k_2b \\ a_1 & b_1 & k_1a_1 + k_2b_1 \\ a_2 & b_2 & k_1a_2 + k_2b_2 \end{vmatrix} &= \begin{vmatrix} a & b & k_1a \\ a_1 & b_1 & k_1a_1 \\ a_2 & b_2 & k_1a_2 \end{vmatrix} + \begin{vmatrix} a & b & k_2b \\ a_1 & b_1 & k_2b_1 \\ a_2 & b_2 & k_2b_2 \end{vmatrix} = 0 + 0 = 0 \end{align} $$\(k_1, k_2\) are arbitrary scalars.

When the determinant is unchanged #

If we add a multiple of one row (column) to another row (column), the determinant remains unchanged. This conclusion is derived from the above conclusion.

$$ \begin{vmatrix} a & c + ka \\ b & d + kb \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} + \begin{vmatrix} a & ka \\ b & kb \end{vmatrix} = \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} + 0 = \begin{vmatrix} a & c \\ b & d \end{vmatrix} $$Singular Matrix #

When the determinant is zero, the matrix is not invertible, also called a singular matrix. This type of matrix compresses the space in some directions, such as compressing three-dimensional space to two dimensions or lower. Once compressed, it cannot be restored because the projection does not reveal the height.

If a matrix is invertible, there exists a standard inverse matrix \(A^{-1}\) that reverses all the transformations it makes.

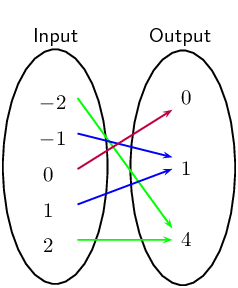

$$ A^{-1}(AB) = (AA^{-1})B = IB = B $$For example, the matrix below compresses two different input vectors to the same output vector. In the many-to-one case, the inverse mapping is impossible.

$$ Av = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = v' = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix} $$$$ Aw = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 2 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = w' = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix} $$

Only by modifying \(A\) to make its determinant nonzero can the inverse mapping be achieved. Because now the input and output are one-to-one.

$$ A'v = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix} $$$$ A'w = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 3 \end{bmatrix} $$In algebra, the reason why a singular matrix does not have an inverse matrix \(A^{-1}\) is that the divisor is zero when calculating the inverse matrix formula, and the calculation cannot be performed. More details in the next article.

$$ A^{-1} = \frac{1}{\det(A)}adj(A) $$Next, continue learning: Understanding Matrix Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors